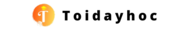

America is increasingly building homes in places endangered by natural disasters. More than half (55%) of homes built so far this decade face fire risk, while 45% face drought risk. By comparison, just 14% of homes built from 1900 to 1959 face fire risk and 37% face drought risk. New homes are also more likely than older homes to face heat and flood risk, but the gap is largest when it comes to fire and drought.

That’s according to a Redfin analysis of climate-risk scores from ClimateCheck and county records on single-family homes built since 1900 that still stand today. We define an at-risk home as one with a ClimateCheck score of moderate, high, very high or extreme. This analysis does not include homes with low or relatively low scores, which may also face some level of risk.

Overall, heat is the most common danger, with nearly 100% of homes constructed in the last two years at risk. Heat risk is based on the number of extremely hot days expected in the future. Next comes storm (78%), followed by fire (55%), drought (45%) and flood (25%). Storm is the only risk more likely to plague older homes. That’s likely because many of the country’s old homes are located in the storm-prone Northeast.

View an interactive Tableau dashboard with this data.

From an environmental standpoint, America is building, rebuilding and subsidizing homes in the wrong places, according to economist Jenny Schuetz, who recently published a book on the topic.

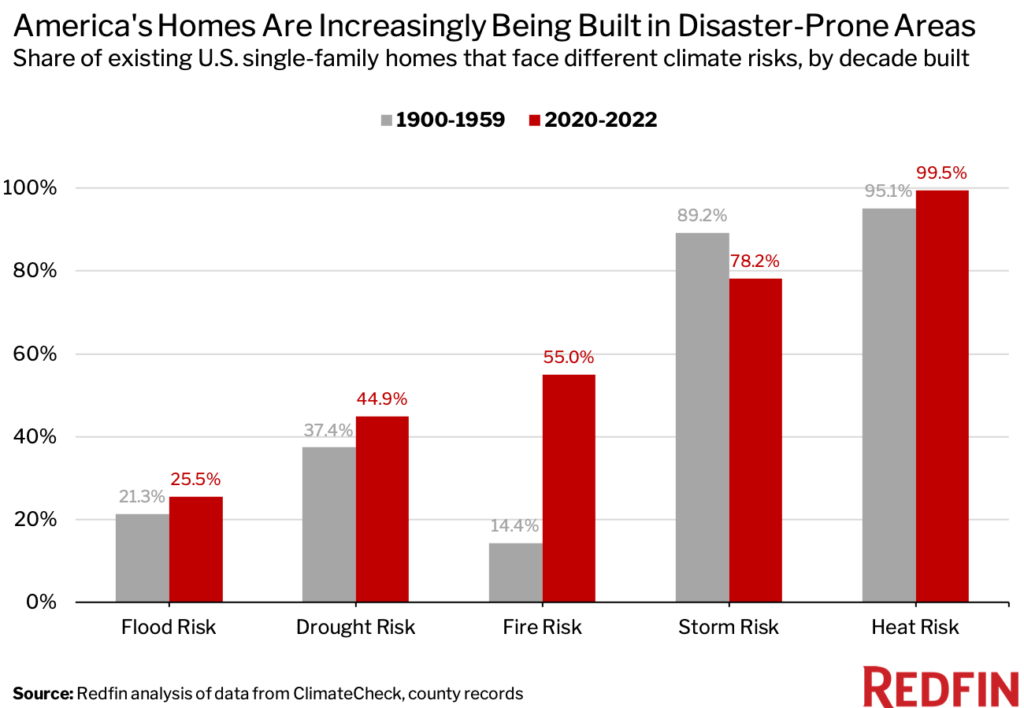

“The areas that are already built are at lower risk of wildfire because they’re not surrounded by forest and trees—they’re surrounded by other buildings,” Schuetz said by phone. But “increasingly, we have to build new housing farther and farther out from downtown areas because the easy-to-use land has been built out and it’s often difficult to add more housing in the urban core. … In the West, the wildfire-prone areas are in the undeveloped lands, and so the farther we push toward the undeveloped lands, the more houses are going to be at risk.”

The push beyond cities intensified after World War II, when interstate highways made it easier for people to live in the suburbs and commute to work. By 2010, more than half of Americans lived in the suburbs, up from 37% in 1970 and 13% in 1940.

Suburbia got another boost during the coronavirus pandemic as builders responded to shifting homebuyer preferences. Remote work and surging housing prices prompted homebuyers to leave high-cost cities for far-flung suburbs and Sun Belt states that often have larger, less expensive houses and more land on which to build. So far this year, the states with the most building permits are Texas, Florida, California, North Carolina, Georgia, Arizona and Colorado—all of which face significant risk from fire, drought, heat and/or flooding. Nationwide, 39.5% of single-family homes built so far this decade are located in the 10 most fire-prone states, compared with 24.3% of homes built from 1900 to 1959.

A 2021 Redfin analysis found that more people have been moving into than out of the U.S. counties with the largest share of homes at high risk of natural disasters. Many of these areas are attracting homebuyers because they’re relatively affordable, have lower property taxes, more housing options or access to nature. Some buyers also just aren’t aware of the risks. That’s partly due to a lack of informational resources, but also because people don’t often see the full cost of disaster when it does occur.

“It’s obviously traumatic if your house burns down in a wildfire or gets hit by a hurricane, but financially, homeowners often get bailed out,” Schuetz said. “If you buy a house, you don’t pay the full amount in cash. You take out a mortgage, so some of the obligation goes to the lender, and you’re required to have homeowner’s insurance that covers you in case of disaster. … Nobody has ownership of this problem.”

Redfin.com publishes climate-risk data for nearly every U.S. home, with the exception of rentals, to help house hunters make more informed decisions. As buyers learn more about climate dangers, they’ll be less inclined to buy in high-risk areas, which will make it challenging for existing owners to sell, Schuetz said. That could ultimately cause home values in some risky places to weaken.

One solution is to encourage people to live in less-risky cities by adding more dense housing and subsidizing public transportation. In many areas, low-density zoning rules limit housing growth close to downtowns, driving builders out to car-dependent, high-risk suburbs, Schuetz wrote in her 2022 book “Fixer-Upper: How to Repair America’s Broken Housing Systems.”

On a federal level, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac could charge higher rates or refuse to securitize mortgages on risky homes, which might disincentivize lenders from writing loans in endangered areas, she added. That option, however, could be politically unpopular and has the potential to keep homeownership out of reach for low-income and minority buyers in high-risk areas. The government could also reexamine tax subsidies like the mortgage-interest deduction, which encourage affluent Americans to purchase pricey homes with big mortgages that are often in the suburbs. Additionally, federal disaster recovery programs could pay more people to rebuild in less-risky locations rather than the same locations. Insurers could also opt to stop issuing policies in dangerous areas, and homeowners and builders in those areas could increase the use of disaster-resistant construction materials.

It’s worth noting that while new homes are increasingly being built in disaster-prone areas, most of America’s housing stock is not new. Two-thirds of U.S. homes were built before 1990, while about 4% were built in 2014 or later, according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates.

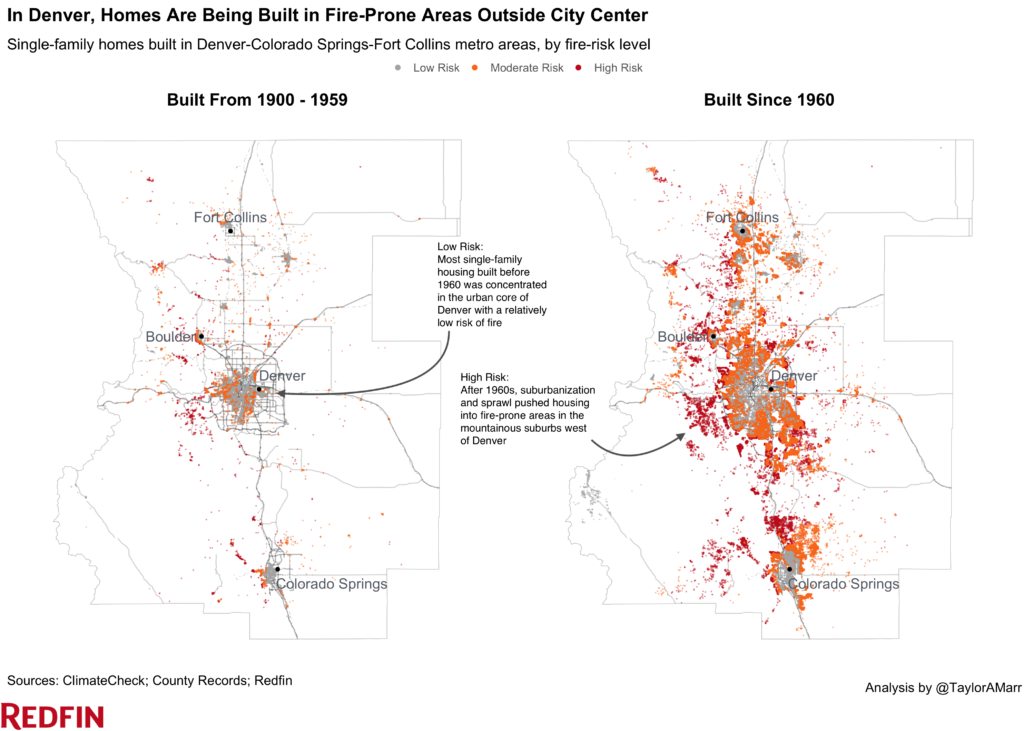

The share of homes constructed in fire-prone areas has been steadily increasing since the 1960s as builders have expanded beyond dense cities and into areas with more flammable vegetation. More than half (55%) of homes built so far this decade face fire risk, compared with 19% of homes built in the 1960s and 8% of homes built from 1900 to 1910.

“There’s no room left to build in Salt Lake City, so developers have been moving into the surrounding mountains, which are more prone to wildfires and drought. Record-breaking temperatures and a lack of snow have turned these areas into tinder boxes,” said local Redfin Market Manager Ryan Aycock. “Herriman—a city just south of Salt Lake City that’s right up against the mountains—is attracting tons of builders. Fires were never that big of an issue when Herriman was mostly vacant land, but now scores of people are moving into harm’s way.”

A fire in 2010 burned more than 4,000 acres and destroyed several homes in the Herriman area after the National Guard conducted a machine-gun training despite fire and wind warnings. Nearly 40% of all Utah homes (roughly $220 billion worth) face high fire risk—a larger share than any other Western state Redfin analyzed in 2021.

The Wildland Urban Interface—parts of the country where houses are close to wildland vegetation (AKA fire risk)—is the fastest growing land-use type in America, with roughly one-third of homes falling in its boundaries. That’s according to a 2018 study led by the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Volker C. Radeloff, who found that the number of new houses in the WUI grew by 41% to 43.4 million from 1990 to 2010. California and Texas have the greatest number of homes in the WUI.

Not only is America increasingly building homes in fire-prone areas—fires are also increasing in intensity. The three most destructive wildfire years, in terms of acreage burned, have all occurred in the last decade, according to the National Interagency Fire Center.

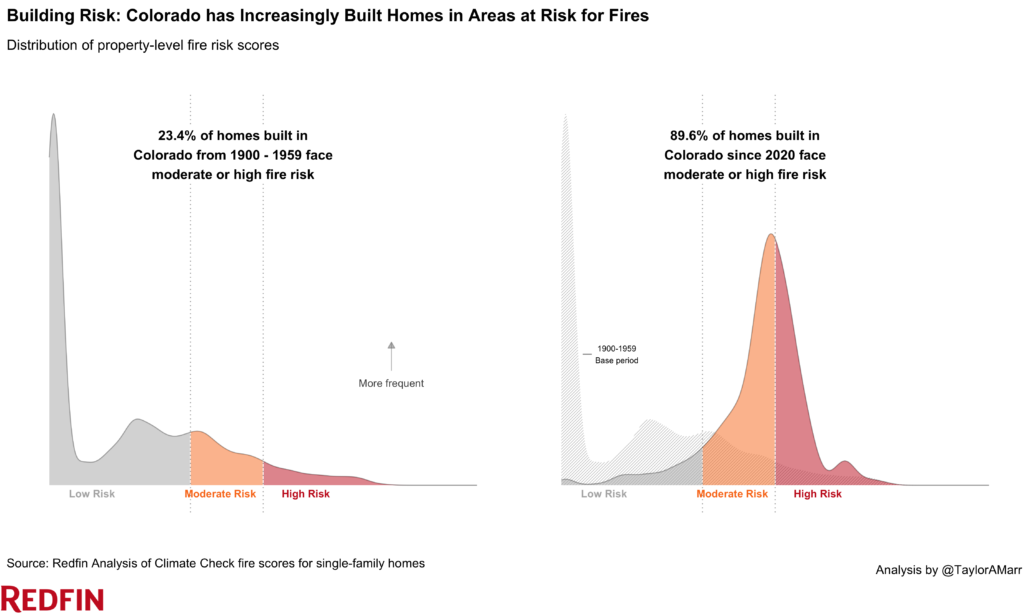

In Colorado, 90% of homes built so far this decade face fire risk, compared with just 23% of those built from 1900 to 1959. That 66-percentage-point gap is the largest among the states Redfin analyzed. Next comes Arizona (97% vs 38%), followed by Utah (85% vs 28%), California (91% vs 39%) and Florida (58% vs 6%).

A significant portion of America’s homebuilding is happening in Florida, California, Arizona and Colorado. Florida has doled out about 133,000 building permits so far this year, more than every state but Texas. California ranks third with 72,000 permits, while Arizona and Colorado rank sixth and seventh, at 40,000 and 33,000, respectively. That’s in part because these states continue to grow. Florida, Arizona and Utah all rank in the top 10 when it comes to percentage growth in population from 2020 to 2021, according to Census estimates. Remote work and surging home prices prompted many Americans to seek out sunny, relatively affordable locales like Miami and Phoenix.

Scroll down to the bottom of this report to view the share of homes in your state facing fire and drought risk.

In Arizona, nearly all homes (97%) built so far this decade face fire risk—a higher share than any other state Redin analyzed. Next comes Oklahoma (96%), Arkansas (94%), Wyoming (93%) and Montana (93%). There are six states—Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.—where no homes built since the start of 2020 are at risk.

Please note that 0% in the table above indicates there are no properties with moderate or high risk; it’s still possible properties face low risk.

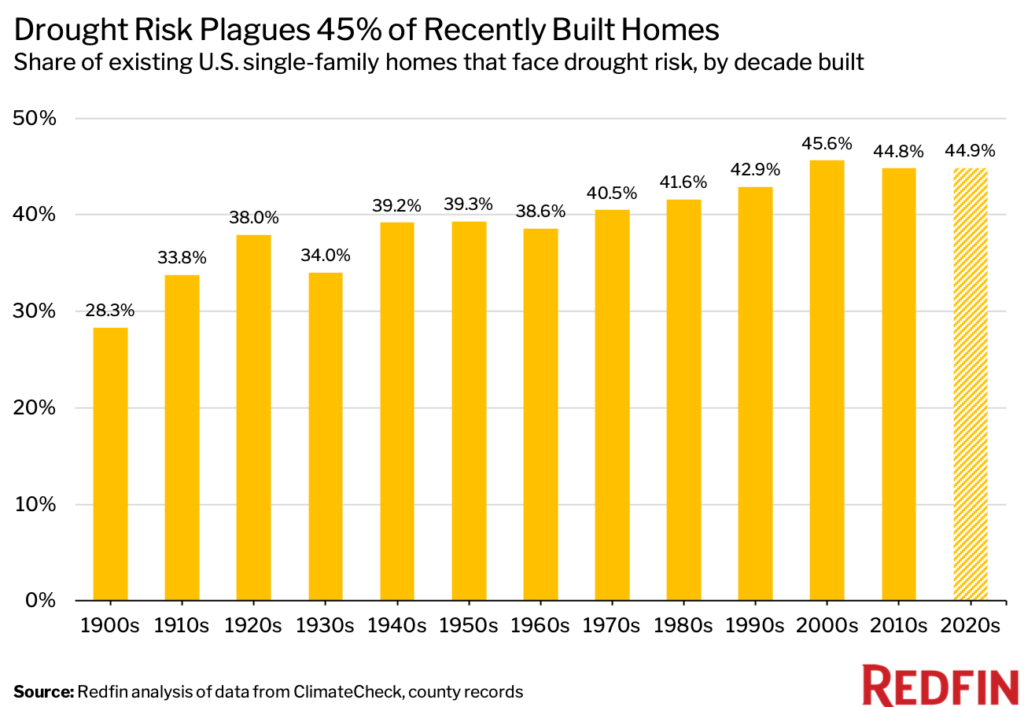

The share of homes constructed in drought-prone areas has also been rising. Just under half (45%) of homes built so far this decade face drought risk, compared with 39% of homes built in the 1960s and 28% of homes built from 1900 to 1910.

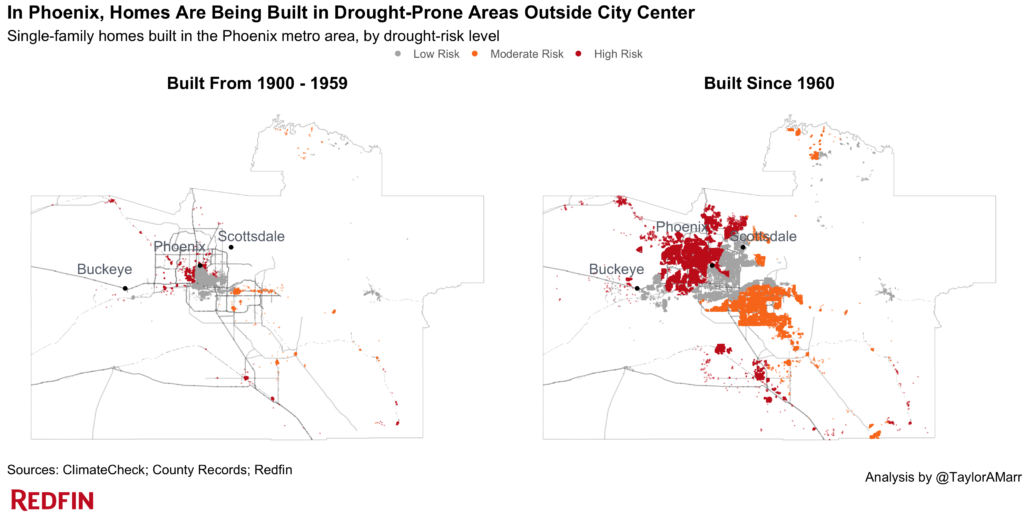

One reason newer homes are more likely to face drought risk is they’re likely to be located in drought-prone states like Texas, California and Arizona. And within those drought-prone states, homes are increasingly being built in neighborhoods that aren’t equipped to handle drought.

“Homebuilding has exploded in Arizona over the last few years as our population has soared. Builders are going to the more rural, drought-prone areas because that’s where there’s available land,” said Phoenix Redfin real estate agent Heather Mahmood-Corley. “In Casa Grande—a city just south of Phoenix—builders are selling homes despite warnings that there may not be enough water to go around. In the nearby San Tan Valley, one developer owns a lot of the wells, so they’re able to build unrestricted and sell water rights to other developers.”

Mahmood-Corley continued: “Builders have done a pretty good job warning buyers about the lack of water, but many buyers don’t think much of it. Oftentimes, they’re more focused on finding an affordable place to live.”

“We have to build additional water infrastructure when we build at the outskirts of cities,” Schuetz said. “Imagine that you build a new subdivision in Arizona; you have to put in things like water lines and sewer lines and roads because they don’t exist in the new subdivision, and of course, all of that requires then using additional water. And so we’re using up the water supply in places like the West because we keep building outside of existing areas rather than adding homes in existing cities.”

Roughly two-thirds of the West experienced extreme drought last summer, and many cities are now grappling with it again, alongside historic heatwaves. The period of 2000 to 2021 was the driest 22-year period since 800 A.D., scientists said.

In Arizona, 75% of homes built this decade face drought risk, compared with 41% of those built from 1900 to 1959. That 34-percentage-point gap is the largest of any state Redfin analyzed. Next comes Pennsylvania (56% vs 28%), Nevada (86% vs 61%), Missouri (29% vs 6%) and Idaho (75% vs 54%).

In Colorado, 100% of homes built this decade face drought risk—the highest share among the states Redfin analyzed. It’s followed by Wyoming (98%), Utah (93%), Nevada (86%) and North Carolina (79%). There are just three states where no homes built since the beginning of 2020 face drought risk: Maine, North Dakota and Washington, D.C. In Kansas and South Dakota, less than 1% of homes built since the start of 2020 face drought risk.

Please note that 0% in the table above indicates there are no properties with moderate or high risk; it’s still possible properties face low risk.

The table below includes the share of homes built from 2020 to 2022 and the share built from 1900 to 1959 that currently face risk from fire and drought. It also includes the change in share (in percentage points) between the two periods. Some figures may appear imprecise due to rounding.

Climate-risk data for drought, fire, flood, heat, and storm comes from ClimateCheck, which assigns six different climate-risk categories to properties across the U.S. (excluding Hawaii and Alaska)—relatively low, low, moderate, high, very high and extreme. For this report, an at-risk property is one that falls into the moderate, high, very high or extreme category for a given climate risk (i.e., a risk score greater than 34). The climate-risk data in this report is as of June 1, 2022 and utilizes the RCP 4.5 emission scenario for assessing future risk. We used county property records to determine when homes were built. The following states were excluded from this analysis due to insufficient county property records: Wisconsin, Louisiana, Vermont, Michigan, Kentucky and New Mexico. We also excluded Missouri and West Virginia due to insufficient property-level climate risk scores.